Abyss

Gallery 2, Seoul-t'ukpyolsi, Seoul, 07/07/2016 - 08/13/2016

657 Sinsadong Gangnamgu Seoul 135-897 Korea

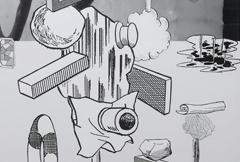

Though it may sound ironic, I will forbid the use of the words ‘Pop Art’ and ‘Atomouse’ in this essay while talking about the artist Lee Dongi. When discussing Lee Dongi, those two terms always appear like the artist’s shadow. How clear and simple it is. However, clarity and simplicity push far away the possibilities of thinking and rediscovery. ‘Seeing’ art is about observing a depicted subject without being confined to a name as if looking at something unfamiliar. Because that is how a painter looks at a subject.

The drawings of Lee Dongi discussed in this essay were created from the 1990s to the late 2000s. These drawings have been collected without necessarily being considered to be put into an exhibition. The more than 200 pieces include sketches for painting and scribbles made without any intention.

Lee’s repetitive practice of drawing characters and patterns which are typical of his work, as well as the process of developing the characters into categories, are interesting. It seems familiar and friendly and simultaneously unfamiliar and strange. And this is what we expect from his exhibitions. Half of the drawings takes the audiences by surprise. They are more like scribbles to kill time than a composition for actual work. We do not know what they represent in what context. The shapes drawn in the corner of a memo pad only connote that his phone call was probably long and boring. Lee Dongi did not discriminate regarding the paper he drew on: from sketch paper, office A4, and ruled notebooks, to ad flyers and exhibition leaflets. The types of paper do not matter when drawing images that suddenly pop up in his head or taking down notes while on the phone.

Images emerging from the subconscious are instant, rough, and always remain incomplete. Drawing is an act of solidifying the artist’s (sub)consciousness that springs up, like the way a word slips out of your mouth. It is established instantaneously. Therefore, we should not conclude that the artist’s drawing is an extension of his painting. Because doing so will exclude the purity of the idea and the spontaneity that drawing can offer. We should always consider that drawings are in a status of being ‘more’ or ‘less’ close to painting. It is not a complete work but the ‘possible status’ of it has the potential to become a work. Though seemingly indifferent, the way this exhibition regularly juxtaposes the process of categorizing the characters is imperfect yet akin to a fluid attitude of drawing. In a separate exhibition room is a bust of Atomouse that was carefully sculpted in a repetitive sculpting process. A sense of hefty volume and weight, and the coldish surface of the bust of Atomouse create a tight tension in confrontation with the rough and improvised drawings, arousing once again the meaning of drawing.

Lee Dongi is concerned with how modern art is generalized into ‘conceptual art.’ The artist said he does not like the binary division between conceptual art and the formal exploration of art. What he said is right. Throughout the history of humanity, no art without a concept has ever existed. However, the discovery of a new term is always phenomenal. A theory or philosophy discovered under the name of ‘conceptual art’ replaced an artistic practice and prioritized the attitude of an artist rather than an artist’s ability to express. And we have come to believe that art is within a concept, non-materialized, and not subordinated to a certain medium such as painting. Drawing, either consciously or not, is a process to give a form, to solidify, and to refine images that are called upon. We call letters written by hand body-writing (肉筆), implying the use of the body in addition to the hand. The drawing of more than 200 pieces may have been a direct/indirect exercise to concretely structure a formative style using the artist’s body. Lee Dongi’s drawings, which generate and review images in a repetition by visiting the deep recesses of the artist’s mind, allude to his view on modern art grounded in a prejudice.

The Elements of Drawing by John Ruskin, a 19th century art critic, described drawing as “a useful tool to deepen the depth of thinking and observation about an object.” The significance of the book lies not in teaching drawing skills, but in contemplating how humanity confronts the outside world and the essence of creative labor through drawing. It is impossible to state or interpret the formative significance of the drawings which have been collected for more than 20 years, because the drawings only convey the artist’s subconscious understanding of the outside world, a way of seeing things, and the process of integrating and refining all this, instead of presenting the theme of the drawings. The way in which the exhibition displays the drawings, indifferent to content, form, and period, is well aligned with the very elements of drawing. The quote from Arthur Schopenhauer, “Every person takes the limits of their own field of vision for the limits of the world,” should be quoted in this context. How have we described and defined Lee Dongi so far? Are these definitions of his work ‘Pop Art’ and ‘Atomouse’ the limits of the artist or our own? Are we ready to meet Lee Dongi as an artist whose work is no longer clear nor simple? Observe depicted objects from a view liberated from notions/terms as if seeing something unfamiliar ? in the way a painter does.

For More Information