Nikki Luna: ManMadeWoman

Silverlens, Philippines, Manila, Manila, 04/30/2014 - 05/31/2014

2F YMC Bldg 2, 2320 Don Chino Roces Avenue Extension

The narrative is in the repetition. A hundred plain white ceramics casted from Barbie coopt her infamous chronicle—a disproportionate naked female figure in need of an endless array of accessories, clothing, et al. This is the premise of Luna’s space: the mutilation of the body vis a vis a desire informed by what it lacks. Luna harnesses the bane of this universal symbol of consumer capitalism to contextualize another hegemon of female representation. The hundred figures are vying for eight crowns. In and around these forms echo questions that do not ask but instead frame ready answers for winning the coveted crowns. These women are spared the need to think and struggle. The stringent standards of who can enter pageants filter to a narrow standardized idea of beauty. And Luna pushes the parody to the hilt by portraying a complete uniformity of the candidates. In this crowd of bodies pared down by a uniform set of desires, no one stands out but homogeneity itself.

Dissenting voices flow around the homogenized bodies. Luna went to a local community surviving despite repeated state-sponsored demolitions to give way to land development for commercial ventures. She asked women residents the pageant questions, “What will you do with a million dollars?” “If given the chance, what part of your body will you change?” The audio recordings start with a silence, presumably as the women looked around their ravaged community, askance at queries far removed from their circumstances. Then a tired response. An account of pressing lack and needs can be heard whispering in a maze of pristine female forms in a likewise antiseptic space. Herein, in the meeting of the two normatives—the objectified female in an aesthete patriarchy, and the struggling proletariat in a neoliberal and neocolonial society—both the bodies and voices piece together a portrayal of the Philippine subaltern. This population is bestowed with a working knowledge of the colonizer’s language enough to understand the questions, trained, exported, controlled, oppressed and displaced but nevertheless, decidedly heterogenous.

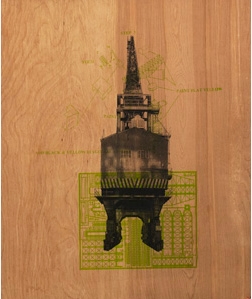

Luna cannot reiterate it enough. The controlled body chooses its battle according to its social status. The artist’s background ranges from fashion to human rights advocacy, a wide spectrum of experience that has recalibrated her view of the Third World women’s struggle. She increasingly incorporates the mingling of concerns of the elite and the workers in her works—from diamonds made of sugar harvested and produced by below-the-minimum wage workers (Hacienda Luisita massacre issue) to a glittering fiberglass backhoe bucket portraying the superficiality of “social-oriented” soirees held in the metropolis for the benefit of a cause thousands of miles and concerns away (Maguindanao massacre issue). The stark differences of paradigms push and pull the focus from form to substance and vice versa. Such dialectical plays produce seamless self-contained fragments that determine Luna’s obvious standpoint. No blood has been drawn but the polished appearances of her pieces pulsate with a growing awareness of the status quo.

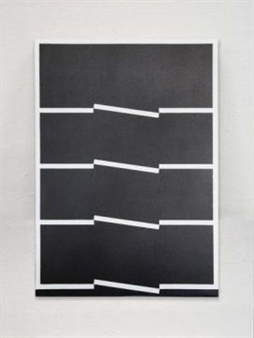

This is where the artist locates her work—on the edge, in between. In Man-Made, the parade of homogenized female bodies questions the celebrity of beauty pageants in a nation rife with socio-economic difficulties. This symbolic subaltern space is given another space within. Luna built a white cube. Inside, the four walls are made of mirrors. A crown dangles in the middle as questions from past Bb. Pilipinas pageants randomly emit from installed speakers. Spectators are invited to participate and stand in the middle. The agency to answer is literally provided for. But the focus is on the act of receiving the processing the questions. The artist is unsure whether the abject—the myriad of female subjugations such as lack of access to education, domestic violence, dearth of reproductive health services and the overarching objectification in a developing society that is, foremost, market-driven—will come through the immaculate installation enough to better inform the answers. Meanwhile, one wonders if one should and/or can assume the same identity as the bodies in the space created by the artist—under the crown, before the judges, appearance appraised, value negotiable, absolutely indeterminate. Then, one looks at the walls, scrambling for an answer and sees one’s own image of irresolution in recollection, the subaltern repeated ad infinitum. The narrative is in the repetition. A hundred plain white ceramics casted from Barbie coopt her infamous chronicle—a disproportionate naked female figure in need of an endless array of accessories, clothing, et al. This is the premise of Luna’s space: the mutilation of the body vis a vis a desire informed by what it lacks. Luna harnesses the bane of this universal symbol of consumer capitalism to contextualize another hegemon of female representation. The hundred figures are vying for eight crowns. In and around these forms echo questions that do not ask but instead frame ready answers for winning the coveted crowns. These women are spared the need to think and struggle. The stringent standards of who can enter pageants filter to a narrow standardized idea of beauty. And Luna pushes the parody to the hilt by portraying a complete uniformity of the candidates. In this crowd of bodies pared down by a uniform set of desires, no one stands out but homogeneity itself.

Dissenting voices flow around the homogenized bodies. Luna went to a local community surviving despite repeated state-sponsored demolitions to give way to land development for commercial ventures. She asked women residents the pageant questions, “What will you do with a million dollars?” “If given the chance, what part of your body will you change?” The audio recordings start with a silence, presumably as the women looked around their ravaged community, askance at queries far removed from their circumstances. Then a tired response. An account of pressing lack and needs can be heard whispering in a maze of pristine female forms in a likewise antiseptic space. Herein, in the meeting of the two normatives—the objectified female in an aesthete patriarchy, and the struggling proletariat in a neoliberal and neocolonial society—both the bodies and voices piece together a portrayal of the Philippine subaltern. This population is bestowed with a working knowledge of the colonizer’s language enough to understand the questions, trained, exported, controlled, oppressed and displaced but nevertheless, decidedly heterogenous.

Luna cannot reiterate it enough. The controlled body chooses its battle according to its social status. The artist’s background ranges from fashion to human rights advocacy, a wide spectrum of experience that has recalibrated her view of the Third World women’s struggle. She increasingly incorporates the mingling of concerns of the elite and the workers in her works—from diamonds made of sugar harvested and produced by below-the-minimum wage workers (Hacienda Luisita massacre issue) to a glittering fiberglass backhoe bucket portraying the superficiality of “social-oriented” soirees held in the metropolis for the benefit of a cause thousands of miles and concerns away (Maguindanao massacre issue). The stark differences of paradigms push and pull the focus from form to substance and vice versa. Such dialectical plays produce seamless self-contained fragments that determine Luna’s obvious standpoint. No blood has been drawn but the polished appearances of her pieces pulsate with a growing awareness of the status quo.

This is where the artist locates her work—on the edge, in between. In Man-Made, the parade of homogenized female bodies questions the celebrity of beauty pageants in a nation rife with socio-economic difficulties. This symbolic subaltern space is given another space within. Luna built a white cube. Inside, the four walls are made of mirrors. A crown dangles in the middle as questions from past Bb. Pilipinas pageants randomly emit from installed speakers. Spectators are invited to participate and stand in the middle. The agency to answer is literally provided for. But the focus is on the act of receiving the processing the questions. The artist is unsure whether the abject—the myriad of female subjugations such as lack of access to education, domestic violence, dearth of reproductive health services and the overarching objectification in a developing society that is, foremost, market-driven—will come through the immaculate installation enough to better inform the answers. Meanwhile, one wonders if one should and/or can assume the same identity as the bodies in the space created by the artist—under the crown, before the judges, appearance appraised, value negotiable, absolutely indeterminate. Then, one looks at the walls, scrambling for an answer and sees one’s own image of irresolution in recollection, the subaltern repeated ad infinitum.