Karmic Abstraction

Bridgette Mayer Gallery, Missouri, Philadelphia, 11/15/2011 - 12/31/2011

ABOUT

PHILADELPHIA – Closed for renovation for much of 2011, Bridgette Mayer Gallery on Washington Square in Center City, Philadelphia, reopens November 15, 2011. The inaugural show in the expanded and transformed space is a group exhibit of contemporary painting, “Karmic Abstraction”.

The show’s title reflects gallerist Bridgette Mayer’s “interest in the idea of the karmic cycle of an artist’s history of painting and ideas.” The selected works, by sixteen nationally- and internationally-recognized artists reveals, “how, at a given moment in time, standing in front of a work of art, the viewer is faced with the multiple layers and concepts that create a painting as well as a lifetime of ideas, actions and history that make up the career and art history of a contemporary artist.”

The term karma derives from a Sanskrit word for “act” and, in Indian philosophy, describes the ways in which good or bad actions reflect on future existence. This interest with painting’s history and how we come to know it is a matter of concern for artists as well as historians, conservators, and audiences. In addition to whatever they depict, paintings are also about the history of their own making, with decisions recorded in brush strokes, patches of raw canvas, under drawing, and pentimenti. It is increasingly common to see X-ray images and other forms of analysis in the exhibition of paintings as old-fashioned connoisseurship is supported by a phalanx of scientific approaches to understanding the history of a picture. (In September of this year, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam announced that they had used florescent X-ray technology to locate a portrait, thought to be of Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother, Joseph, under Goya’s 1823 portrait of Don Ramón Satué.)

The artists in the exhibit reflect notions of how the history of a painting might be apparent on its surface in a number of ways. Some works speak to personal or cultural memory, while others address the traditions of painting or the medium’s capacity to generate a record of its own creation.

Atlanta-based artist Radcliffe Bailey situates his work in dialog with the past by incorporating photographs into his compositions. Odili Donald Odita, a Philadelphia painter, uses color to “reflect the collection of visions from […] travels globally and locally”. Philadelphian Tim McFarlane writes that “relationships between time, memory, and movement form the primary foundation” for his paintings, which have an atmospheric quality as if seen through a filter of recollection. For each of these artists, paintings are a repository for personal and cultural experience and means of reflecting on questions of identity.

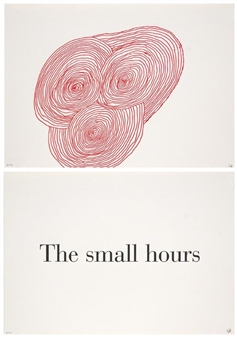

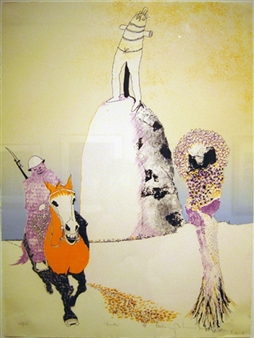

Neil Anderson, of Lewisburg, PA, makes paintings that seek to stop time, arresting it at a moment of ideal formal balance. This notion of using painting – the original slow-media – as means of controlling time and pausing at a critical moment, resonates with other artists in the exhibit. Philadelphian Nate Pankratz describes his painting process as an ‘editorial’ one in which shapes are shifted, repositioned, and rearranged, imparting a sense of time and careful revision in the final works. In stark contrast to such deliberation, Los Angeles-based Iva Gueorguieva’s pictures are built of forms that one writer described as, “barely revealed and poised to disintegrate”. Korean-born, London-based painter Eemyun Kang shares an interest in pictorial instability (as Rebecca Rose notes in her essay, Topography of Flux). Arden Bendler Browning (of Philadelphia) also makes paintings that appear on the edge of flying apart, owing to the way they reflect on the artist’s technology-inspired navigation of the urban landscape.

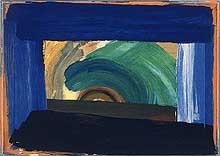

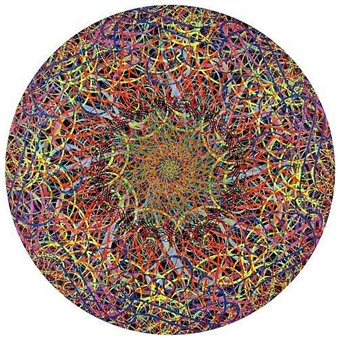

The idea of a painting’s history becoming apparent through familiarity, quotation, or use of borrowed images is also a theme that runs through the exhibit. Philadelphia painter Rebecca Rutstein, whose use of undersea mapping and other geological imagery has earned attention for her earlier works, turns her eye to space exploration in a new body of work. Spatial images – those of black holes in outer space as well as the spiritual spaces of 16th century Italian paintings (such as Antonio da Correggio’s Assumption of the Virgin) – have influenced New York painter Ryan McGinness, creating a swirling confluence of past and future. Others in the exhibit wear their historical connections in more general and allusive ways. New Yorker Leslie Wayne writes of her fascination with 19th century Romantic landscape painters and how their awe before nature is translated into materials-rich abstraction in her practice. It is the history of painting’s use of figuration that inspires Matthew Fischer (another New Yorker), whose aim is to make “abstract paintings that have the pictorial grip of representational paintings: the grip of figure/ground relationships, the grip of volume and atmosphere within imaginary space.” Graeme Todd, of Edinburgh, Scotland, also notes that his “way into art wasn’t through nature, it was through art” and discusses the way ideas suggested by German Renaissance etchings crop up in his taut, layered abstractions.

The value of layering as a means of communicating a painting’s history is also recognized by Philadelphia painter Charles Burwell, whose compositions layer linear, labyrinthine, and biomorphic imagery. Though his works are rich in cultural and historical associations, Burwell is primarily concerned with a painting’s construction, and as such, his works are records of their own imagining, difficult to pin down using language. Los Angeles artist Joe Goode’s long career of exploring various media and images approaches layering in a different way – calling up and revisiting images from his past through photography and self-quotation. “As an artist, you’re always creating your own history,” Goode said in a 2008 gallery lecture. Painter Thomas Nozkowski (New York) also creates work that evades language in its pictorial complexity and richness. Talking about his paintings with writer Francine Prose in an interview, Nozkowski remarked:

The central fact of our lives, of any artist’s life, are the thousands upon thousands of hours we spend alone staring at these damn things, thinking about them. We sit there, and these things just go on, and on, and on. Everything in the world ties into them, everything that’s crossed your mind while you’re working on it. And, if somebody could just get a sense of that fullness in a work of art, it’s working, you’re on the right track.

This notion – that “everything in the world ties into them, everything that’s crossed [an artist’s] mind” seems central to the exhibit as an opportunity to look at abstract painting as a means of exploring the history of objects and artists.

For More Information

PHILADELPHIA – Closed for renovation for much of 2011, Bridgette Mayer Gallery on Washington Square in Center City, Philadelphia, reopens November 15, 2011. The inaugural show in the expanded and transformed space is a group exhibit of contemporary painting, “Karmic Abstraction”.

The show’s title reflects gallerist Bridgette Mayer’s “interest in the idea of the karmic cycle of an artist’s history of painting and ideas.” The selected works, by sixteen nationally- and internationally-recognized artists reveals, “how, at a given moment in time, standing in front of a work of art, the viewer is faced with the multiple layers and concepts that create a painting as well as a lifetime of ideas, actions and history that make up the career and art history of a contemporary artist.”

The term karma derives from a Sanskrit word for “act” and, in Indian philosophy, describes the ways in which good or bad actions reflect on future existence. This interest with painting’s history and how we come to know it is a matter of concern for artists as well as historians, conservators, and audiences. In addition to whatever they depict, paintings are also about the history of their own making, with decisions recorded in brush strokes, patches of raw canvas, under drawing, and pentimenti. It is increasingly common to see X-ray images and other forms of analysis in the exhibition of paintings as old-fashioned connoisseurship is supported by a phalanx of scientific approaches to understanding the history of a picture. (In September of this year, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam announced that they had used florescent X-ray technology to locate a portrait, thought to be of Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother, Joseph, under Goya’s 1823 portrait of Don Ramón Satué.)

The artists in the exhibit reflect notions of how the history of a painting might be apparent on its surface in a number of ways. Some works speak to personal or cultural memory, while others address the traditions of painting or the medium’s capacity to generate a record of its own creation.

Atlanta-based artist Radcliffe Bailey situates his work in dialog with the past by incorporating photographs into his compositions. Odili Donald Odita, a Philadelphia painter, uses color to “reflect the collection of visions from […] travels globally and locally”. Philadelphian Tim McFarlane writes that “relationships between time, memory, and movement form the primary foundation” for his paintings, which have an atmospheric quality as if seen through a filter of recollection. For each of these artists, paintings are a repository for personal and cultural experience and means of reflecting on questions of identity.

Neil Anderson, of Lewisburg, PA, makes paintings that seek to stop time, arresting it at a moment of ideal formal balance. This notion of using painting – the original slow-media – as means of controlling time and pausing at a critical moment, resonates with other artists in the exhibit. Philadelphian Nate Pankratz describes his painting process as an ‘editorial’ one in which shapes are shifted, repositioned, and rearranged, imparting a sense of time and careful revision in the final works. In stark contrast to such deliberation, Los Angeles-based Iva Gueorguieva’s pictures are built of forms that one writer described as, “barely revealed and poised to disintegrate”. Korean-born, London-based painter Eemyun Kang shares an interest in pictorial instability (as Rebecca Rose notes in her essay, Topography of Flux). Arden Bendler Browning (of Philadelphia) also makes paintings that appear on the edge of flying apart, owing to the way they reflect on the artist’s technology-inspired navigation of the urban landscape.

The idea of a painting’s history becoming apparent through familiarity, quotation, or use of borrowed images is also a theme that runs through the exhibit. Philadelphia painter Rebecca Rutstein, whose use of undersea mapping and other geological imagery has earned attention for her earlier works, turns her eye to space exploration in a new body of work. Spatial images – those of black holes in outer space as well as the spiritual spaces of 16th century Italian paintings (such as Antonio da Correggio’s Assumption of the Virgin) – have influenced New York painter Ryan McGinness, creating a swirling confluence of past and future. Others in the exhibit wear their historical connections in more general and allusive ways. New Yorker Leslie Wayne writes of her fascination with 19th century Romantic landscape painters and how their awe before nature is translated into materials-rich abstraction in her practice. It is the history of painting’s use of figuration that inspires Matthew Fischer (another New Yorker), whose aim is to make “abstract paintings that have the pictorial grip of representational paintings: the grip of figure/ground relationships, the grip of volume and atmosphere within imaginary space.” Graeme Todd, of Edinburgh, Scotland, also notes that his “way into art wasn’t through nature, it was through art” and discusses the way ideas suggested by German Renaissance etchings crop up in his taut, layered abstractions.

The value of layering as a means of communicating a painting’s history is also recognized by Philadelphia painter Charles Burwell, whose compositions layer linear, labyrinthine, and biomorphic imagery. Though his works are rich in cultural and historical associations, Burwell is primarily concerned with a painting’s construction, and as such, his works are records of their own imagining, difficult to pin down using language. Los Angeles artist Joe Goode’s long career of exploring various media and images approaches layering in a different way – calling up and revisiting images from his past through photography and self-quotation. “As an artist, you’re always creating your own history,” Goode said in a 2008 gallery lecture. Painter Thomas Nozkowski (New York) also creates work that evades language in its pictorial complexity and richness. Talking about his paintings with writer Francine Prose in an interview, Nozkowski remarked:

The central fact of our lives, of any artist’s life, are the thousands upon thousands of hours we spend alone staring at these damn things, thinking about them. We sit there, and these things just go on, and on, and on. Everything in the world ties into them, everything that’s crossed your mind while you’re working on it. And, if somebody could just get a sense of that fullness in a work of art, it’s working, you’re on the right track.

This notion – that “everything in the world ties into them, everything that’s crossed [an artist’s] mind” seems central to the exhibit as an opportunity to look at abstract painting as a means of exploring the history of objects and artists.